This post follows my path to discovering a passion for accessibility and landing my dream job as an accessibility engineer.

Starting out on rocky flats (2000-2007)

It took me several years to become a decent web developer. Self-taught, I learned HTML through view source on webpages; I used code snippets from online tutorials; I built nested tables for layout. As the browser wars raged, most people didn’t care if the code was good so long as the website looked pixel perfect.

During university, my plan was to be a high school English teacher. My last semester, I realized I enjoyed coding more and would make a better wage building websites. Two months after graduating, I started my first full-time tech job. I got hired because I was the only candidate with any web experience. Acting as designer, developer and content author, I built the first website for a small manufacturing company in late 2000 as the dot com bubble burst.

After a couple of months, life took me to California where I got my second web developer role, this time for a manufacturing software company. I distinctly remember coming in to interview and having to do a coding test to prove I knew HTML. In this job, I learned how to work on multiple projects and maintain several different websites. I helped them with their first website redesign, as well as create a separate website for user conferences.

I spent most days fielding requests to update website content. Towards the end of my six years at QAD, I learned about portal and content management systems (CMS) as we went through a second redesign. This helped me get my next web developer job, which was at the CMS company, back in Texas.

Hiking through the forest (2007-2012)

It was 2007 and I needed to know CSS for the task of redesigning a website from a table-based layout and static HTML into a CSS-based layout with content in a CMS. I picked up a book that changed my life.

Designing with Web Standards

For a self-learner like me, Zeldman’s seminal book helped several pieces fall into place. I learned web standards were a thing and there were actual guidelines for creating semantic webpages. I learned CSS and how to keep design separate from content. I started reading two newsletters: A List Apart and Sitepoint. My world just opened up when I found all these people writing about the web standards way of doing things. I had my first introduction to accessibility in this 2007 article, JavaScript and Screen Readers.

I learned from a co-worker that the University of Texas at Austin had a program with an “information architecture” (IA) track and in 2009 I started graduate work on a Master of Science in Information Studies degree (a.k.a. library school). The curriculum wasn’t as robust as I hoped, but it gave me a flexible framework to explore my interests around usability and accessibility. After 3.5 years of working full-time and going to school part-time, I graduated in 2012 with an endorsement of specialization in user experience design (UXD). This included two courses on making systems work for people with disabilities.

It was around this time that mobile browsing and responsive design were getting real attention from the development world, along with HTML5 and CSS3. I incorporated these technologies in my projects but my career desires were shifting left from developing to designing. I wanted to do user experience design work.

Switchback up the north face (2012-2020)

I tried for years to improve our user experience process at work. I advocated for creating prototypes and using those for low-fidelity usability testing of all our application changes. There was interest but no commitment. While I was able create more functional design documentation over time, we had only one project that included personas, wireframes and testing with end users.

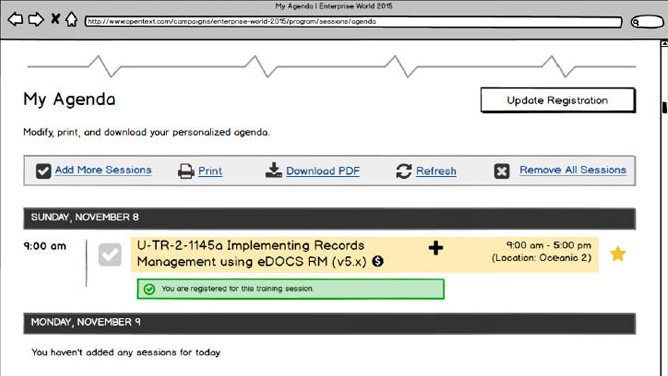

In 2015, I shifted my focus again, this time to accessibility. I performed the first accessibility audit of OpenText’s corporate website using the W3C’s Web Accessibility Initiative Easy Checks – A First Review of Web Accessibility. In retrospect, this was a transformative act because it started the accessibility conversation with Marketing and IT at OpenText. I also started my blog which let me explore usability and accessibility issues in the wild, improving my auditing skills.

I learned as much about accessibility as I could through webinars, online courses, Twitter and conferences. I’m very lucky to live in Austin where the AccessU accessibility conference is held each spring. In 2018, I learned about the International Association of Accessibility Professionals (IAAP) and certifications available. In 2019, I passed the exam for the Web Accessibility Specialist credential after years of checking websites and fixing accessibility issues.

Integrating accessibility at work was slow going with many struggles. In 2020, I started looking for a job with an accessibility-focus, somewhere that accessibility is valued and non-negotiable. Just after I took the next IAAP exam, Certified Professional in Accessibility Core Competencies, COVID-19 interrupted everything. I decided to halt my job search until 2021 to see whether OpenText would come into compliance with the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA) by 1 January.

Reaching the summit

The new year came without any firm support for an accessibility program in IT, however Marketing pledged not to publish any new content that does not conform to WCAG 2.0 level AA, which I consider a huge win.

On the side, I picked up an accessibility contracting job and had my first exposure to a robust accessibility testing methodology. Another piece fell into place and I learned so much in six weeks about the process of testing as well as how to test native mobile applications. Soon after, I started interviewing for an accessibility engineer position at another accessibility firm.

I wanted a remote-only position after all this time working from home during the pandemic. I wanted a raise. I wanted to find meaningful work. And I got the job! I’m very excited to start this next chapter of my accessibility journey.

In my exit interview, I let my former employer know that I didn’t feel right working on websites that excluded disabled people. It felt good taking a stand and finding work that will improve information access for everyone.