This week, I gave a presentation about web accessibility to the content authors of our corporate marketing website who combine text, images, video, etc. into web pages using a content management system (CMS). I’ve found it challenging to tailor web accessibility information for different audiences (developers versus content authors) including how to break it into manageable chunks that go just deep enough during an hour-long meeting to keep folks engaged while encouraging them to learn more on their own.

I began by asking for their help. Our content authors are the people interacting with the website most frequently and they are in a prime position to uncover and report issues, including limitations of the CMS. As they learn and practice web accessibility, my hope is that we are able to use their questions and concerns to grow a culture of accessibility in the company.

What is web accessibility?

Definitions of web accessibility often frame it as a way of making the Web work for people with disabilities but that framing has started to seem problematic because it focuses on disability instead of acknowledging that all of us experiences the Web with a range of preferences and abilities.

Web accessibility is creating websites and web applications that are inclusive of as many people as possible.

No matter what digital space we’re designing for, we must make the choice to be inclusive by having a clear awareness of the diversity of our users and their interaction preferences.

Web accessibility benefits everyone

While improving information access for people with permanent disabilities like low vision, hearing loss and fine motor control tends to be the main focus of web accessibility, accessible design creates a better experience for all of us by also supporting

- Changing abilities due to ageing, like needing larger text size. Every day, I find myself using CTRL++ to make web pages easier to read.

- Temporary disabilities such as a broken arm or lost glasses. Any of us at any time can experience a change in ability.

- Situational limitations like using a screen in bright sunlight or watching video with the sound muted. I use video captions all the time, though I don’t have a hearing impairment.

- Limited bandwidth or a slow Internet connection. Millions of people, even around major metropolitan areas in the US, don’t have high speed internet access (2019, Pew Research Center Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet).

Accessibility is a civil right

People are excluded from every aspect of society when we don’t design and build in accessible ways. We infringe on the privacy and security of our users if they must depend on help from others to interact with our websites and web applications. Many law-making bodies are writing and passing legislation to help address the problem of public accommodation and equal access:

- United Nations: Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- Canada: Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, 2005 (AODA)

- United States: Americans with Disabilities Act, 1990 (ADA)

- European Union: EN 301 549 Directive on the Accessibility of Websites and Mobile Applications

We have a responsibility to provide our users with accessible information and it’s very doable when we think about accessibility as design methodology.

Disability is never a barrier.

Haben Girma, first deafblind graduate of Harvard Law School

Design is.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines

I work for a Canadian company that must comply with the AODA which references the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). WCAG is a set of best practices for improving information access that has been around since 1999. The 13 guidelines are categorized by four principles:

Perceivable

Information and user interface components must be presentable to users in ways they can perceive.

- Guideline 1.1 – Text Alternatives: Provide text alternatives for any non-text content so that it can be changed into other forms people need, such as large print, braille, speech, symbols or simpler language.

- Guideline 1.2 – Time-based Media: Provide alternatives for time-based media.

- Guideline 1.3 – Adaptable: Create content that can be presented in different ways (for example simpler layout) without losing information or structure.

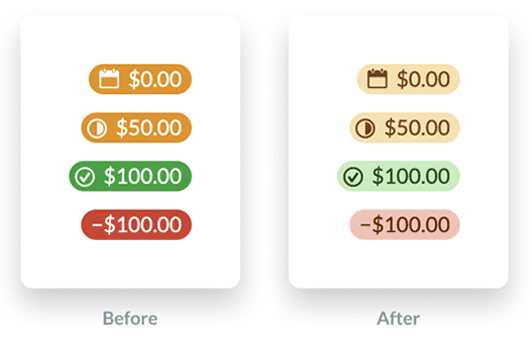

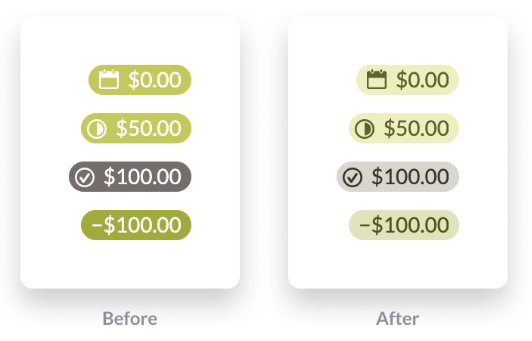

- Guideline 1.4 – Distinguishable: Make it easier for users to see and hear content including separating foreground from background.

Operable

User interface components and navigation must be operable.

- Guideline 2.1 – Keyboard Accessible: Make all functionality available from a keyboard.

- Guideline 2.2 – Enough Time: Provide users enough time to read and use content.

- Guideline 2.3 – Seizures and Physical Reactions: Do not design content in a way that is known to cause seizures or physical reactions.

- Guideline 2.4 – Navigable: Provide ways to help users navigate, find content, and determine where they are.

- Guideline 2.5 – Input Modalities: Make it easier for users to operate functionality through various inputs beyond keyboard.

Understandable

Information and the operation of the user interface must be understandable.

- Guideline 3.1 – Readable: Make text content readable and understandable.

- Guideline 3.2 – Predictable: Make Web pages appear and operate in predictable ways.

- Guideline 3.3 – Input Assistance: Help users avoid and correct mistakes.

Robust

Content must be robust enough that it can be interpreted reliably by a wide variety of user agents, including assistive technologies.

- Guideline 4.1 – Compatible: Maximize compatibility with current and future user agents, including assistive technologies.

Creating accessible content

The accessibility focus for our content authors using a CMS to build web pages is different than the focus of the front-end developers creating the templates, themes and widgets that comprise the basics of a website. Just as I am typing this post into a text editor in WordPress, rarely touching any HTML, our content authors aren’t usually coding; they are marking up text and inserting media through a GUI.

Their concern is evaluating individual web pages, not the website on the whole. They need to be able to identify and remediate issues in their content that differs from site-wide issues with repeated elements in the header and footer or problems introduced by CSS.

Checklists

The AODA specifically requires WCAG version 2.0, level AA conformance for a total of 36 success criteria. When I was first learning about these, I found it really overwhelming. I still find the WCAG format intimidating because there is just so much information to reference. Thankfully, many people and organizations have created checklists that present the success criteria in simpler ways.

- Easy Checks: A first review of web accessibility that breaks out the basics for beginners. I used this streamlined list when I did the first accessibility audit of our corporate marketing website.

- The A11y project checklist: Uses plain language suggestions of what to review by content type like images, forms, headings and tables.

- WebAIM checklist: A comprehensive checklist organized by success criteria and supplemented with clear examples. WCAG 2.1 updates are included and highlighted.

Accessibility testing

Testing is imperative so it’s important to find tools that work for you. The choices are vast and most tools run similar checks against the same WCAG success criteria. For content authors, I suggest trying WAVE (the Web Accessibility Evaluation Tool) which can be added to Chrome and Firefox as a browser extension. It provides a simple, graphical overlay showing automated testing errors in context. Additionally, it exposes hidden data like heading order and alt text that aids in manual testing.

Passing an automated test doesn’t mean a page is accessible. For example, automated tools can detect that an <img> element has an alt attribute, but they can’t decide if it’s good alt text.

Automated accessibility testing tools can catch only about 30% of possible errors.

Manual testing tips

- Review alt text and link text for meaning

- Tab through the content to check focus visibility

- Ensure you can use the web page with only a keyboard

- Learn to use a screen reader. I test on Windows with the free NVDA software. MacOS includes VoiceOver. (See: Screen reader keyboard shortcuts and gestures)

Get started with web accessibility

Check out the W3C’s Web Accessibility Initiative website with strategies, standards and supporting resources to help you make the Web more accessible. The “Accessibility Fundamentals” section includes:

- Introduction to Accessibility

- Components of Web Accessibility

- Accessibility Principles

- Perspectives Videos

- Accessibility, Usability, Inclusion

The power of the Web is in its universality.

Tim Berners-Lee, W3C Director and inventor of the World Wide Web

Access by everyone regardless of disability is an essential aspect.